Stopping Redirects

This post will cover various ways to cancel or pause redirects in the browser, since I’ve recently come across some interesting tricks that let you do this in different situations.

Use cases

Redirects are awesome, I hear you say, why would we want to stop them?

Well, dear reader I made up, there are some niche uses for these tricks to help in situations that are otherwise barely unexploitable. I’ll go through 2 reasons here that I’ve personally seen, but simply knowing these ideas may allow you to apply them to other cases.

First, one common use case is performing the OAuth “dirty dance” technique through an XSS vulnerability you found using JavaScript. It requires two things:

- A way to leak the callback URL with the

?code=parameter in it - To stop the code from being used once the URL is fetched, something has to go wrong in the flow, while we are still able to catch it

The first is easy with XSS, we just read location.search and extract the code from there. The second point varies a lot per application, but this is just what stopping redirects is useful for. The callback URL we want to leak is redirected to. If we can prevent it from getting there, we should be able to exfiltrate and use the code for ourselves to log into the victim’s account.

Another situation is when a vulnerability you found requires user interaction, so you want to give the user time to perform that interaction. But if the page redirects away too quickly, you may not have a practical attack. We want to stop the redirect and render the vulnerable page clearly to the user.

There’s also an important distinction to make between Server-Side and Client-Side redirects. The former is using a 30X status code with the Location: response header, while the latter happens via JavaScript with the location.href setter or navigation.navigate(), or even using HTML with a <meta http-equiv="refresh"> tag.

Some of these tricks will work only on the server-side, others only on the client-side. Take careful note of exactly how yours works.

Control of URL?

If you have (partial) control over the URL, alter it to cause the browser to refuse the redirect.

For example, some special protocols can’t be redirected to. This varies by browser, and the behavior is not the same across all of them. Here are some facts:

- The

data:protocol is only allowed to be client-side redirected to inside an iframe, trying to do so top-level will not do anything. - The

about:protocol gets replaced byabout:blank#blockedin chrome, while on Firefox it throws a JavaScriptTypeError - The

resource:protocol in server-side redirects used to render body on Firefox, but now errors 😔. The only way for a server-side redirect to render its body is now in Chrome, with theLocation:header being completely empty.

These all assume you have control over the start of the URL, but what if your input is somewhere in the middle of the URL when the https: protocol was already given? There are a few more tricks that can be applied.

Specifically, in a Client-Side redirect, @kire_devs_hacks mentioned in Discord that Chrome’s Dangling Markup protection detects < together with \n or \t in a URL and will block the request, including navigations. The following will fail to redirect:

<script>

location = "https://example.com/<\t"

</script>

Another idea is overflowing the URL with so much data that the server can’t handle it, and quickly returns an error page instead. In the case of leaking OAuth codes, you might be able to do this with a very large state= parameter that is reused in the callback request. The code will not be used because the server couldn’t handle the request, but the resulting page will still be same-origin, so you can read its location.search.

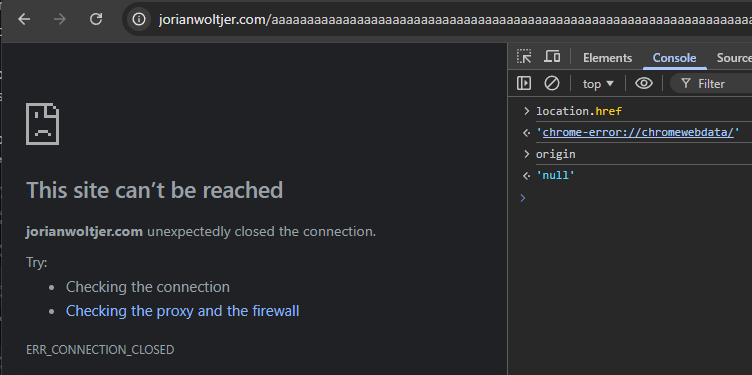

PS. This is also just an interesting tip in general, while testing, I managed to get 5 different error pages on my own site for varying URL lengths:

- 1000:

500 Internal Server Error- 10000:

414 Request-URI Too Largenginx/1.28.0- 33000: Cloudflare UI

Error 1036Invalid request rewrite- 70000:

414 URI Too Long- 200000: Built-in

ERR_CONNECTION_CLOSED

The browser itself also has a hard limit on URL length of 2MB. Any bigger than this and it just gets replaced by about:blank#blocked, and we can’t do anything with it.

Fun fact: this limit even includes the # hash fragment, which is kept across same-origin navigations. This can be useful in XS-Leaks to detect the length of some other part of the URL!

Leaking built-in error pages

Above, we got one ERR_CONNECTION_CLOSED error, which displayed a built-in error page when our URL was so long that the server simply refused to connect.

But when we check the location.href and origin, it becomes clear that this page is no longer same-origin. If we had a window reference to it, we could not read its location.search to find the code parameter or anything.

Luckily, because this was a same-origin redirect, there is another trick we can use to still leak the URL. Even though the document may be cross-origin, the URL is still saved in history. We can read this history using the Navigation API by simply redirecting to some page we have access to and then reading the saved navigation.entries() (only supported in Chrome as of now).

Try running the following in your DevTools Console on https://example.com:

w = window.open("/?" + new URLSearchParams({

state: "A".repeat(100000), // Cause Built-in ERR_CONNECTION_CLOSED error page

code: "SECRET"

}));

setTimeout(() => {

const interval = setInterval(() => {

w.location = "about:blank";

try { // Wait for it to become same-origin

w.origin;

clearInterval(interval);

} catch {return}

// Now we can read history to find errored URL

alert(w.navigation.entries()[0].url.split("code=")[1]);

}, 100);

}, 3000); // Let it fail to connect once to save the URL in history

Another common error page this trick is useful for is the 431 Request Header Fields Too Large status code, which is pretty self-explanatory. The documentation even mentions common ways this may happen:

- The

RefererURL is too long- There are too many Cookies sent in the request

We can trigger either of these using XSS, although sending a large Referer: header is hard nowadays because browsers limit it to 4096 bytes.

Cookies are a more common way of doing this in a technique called “cookie bombing”. Using JavaScript, we can set document.cookie to create a bunch of large cookies, which are always sent in the Cookie: request header. When this becomes too large, it can error and not use the code.

By setting these cookies with a specific Path= attribute, you can even selectively block certain URLs while keeping others working. We’ll target just the redirect destination.

for (let i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

document.cookie = `filler${i}=${'A'.repeat(4000)}; Path=/callback`;

}

This will send a gigantic 400KB of headers, which some servers handle by refusing to connect again, but others return specific status codes like 431. Both can be leaked with the same JavaScript snippet as above.

Triggering WAF

One more creative idea to trigger error pages is using the Web Application Firewall (WAF) living over top of many mature applications.

@hakupiku shared this idea where you put some dangerous text like <script>alert(1)</script>, the state parameter again in an OAuth flow. When it’s reflected in the /callback URL, the firewall may block it and return a generic page instead. This keeps the code fresh for us to steal again through our window reference and location.search.

If there is no state parameter or it is strictly validated, the above “cookie bombing” idea can also be applied on a smaller scale to just inject a dangerous-looking cookie into the request, which will be blocked by the WAF when you request the selected path.

Max redirects

To prevent infinite loops, the browser imposes a limit of 20 server-side redirects before stopping with ERR_TOO_MANY_REDIRECTS. Unfortunately for us, it stops before the last redirect, so if we would look at the location.href, then it would still be the URL right before the callback (unless it redirects multiple times with the code inside the URL).

There is a different limit for client-side redirects, however, discovered by @RafaX during an awesome bug story. When a page issues 200x navigations within 10 seconds (source), the browser blocks any further navigations during that period. This is true for both Chrome and Firefox.

<script>

for (let i = 1; i < 250; i++) {

location.hash = i;

// After #200, warning "Throttling navigation to prevent the browser from hanging" appears

}

</script>

In Chrome < 142 and the latest Firefox, this count is kept across same-site navigations. That means that if you are able to quickly trigger 199 navigations before going to your target page, that target page is not allowed to instantly client-side redirect. The navigation needs to be initiated by a same-site website, many times within 10 seconds. We have to use an XSS on a subdomain or find gadgets to trigger it remotely, like via hashchange or postMessage() handlers.

Here’s an example gadget using postMessage():

onmessage = (e) => {

if (e.data === "redirect") {

location = "/redirect";

}

}

This is exploitable by opening it first, triggering many navigations, and then finally navigating it to the page whose redirect we want to stop. As an example, take the following situation where we want to let the user click the button.

<script>

location = "/away"

</script>

<button onclick="alert('Yay!')">Click me</button>

Right when this location = "/away" executes, the tab reaches its limit, and the client-side redirect will be denied. The rest of the page renders, and the user can click our button!

<script>

const gadget = "https://r2.jtw.sh/poc.html?body=%3Cscript%3E%0D%0A%09onmessage+%3D+%28e%29+%3D%3E+%7B%0D%0A%09++if+%28e.data+%3D%3D%3D+%22redirect%22%29+%7B%0D%0A%09++++location+%3D+%22%2Fredirect%22%3B%0D%0A%09++%7D%0D%0A%09%7D%0D%0A%3C%2Fscript%3E";

const vuln = "https://r.jtw.sh/poc.html?body=%3Cscript%3E%0D%0A%09location+%3D+%22%2Faway%22%0D%0A%3C%2Fscript%3E%0D%0A%3Cbutton+onclick%3D%22alert%28%27Yay%21%27%29%22%3EClick+me%3C%2Fbutton%3E";

const w = window.open(gadget, "", "width=800,height=300");

setTimeout(() => {

for (let i = 0; i < 200; i++) {

w.postMessage("redirect", "*");

}

setTimeout(() => {

w.location = vuln;

}, 0);

}, 1000);

</script>

allow-forms sandbox

The trick that inspired me to write this post was a real-world bug I found during a recent pentest. Arbitrary input was reflected in an <a href= (correctly escaped), but the page was quickly being navigated away by a <form> that auto-submits.

Using this input, I wanted to let the user click on the link to execute JavaScript: ?nextUrl=javascript:alert(origin)

<form action="/some-handler-doing-serverside-redirect">

<input type="hidden" name="nextUrl" value="javascript:alert(origin)">

</form>

<script>

document.forms[0].submit();

</script>

<a href="javascript:alert(origin)">Click this link if you do not automatically get redirected</a>

I could see the vulnerable link for a split second before it just redirects away, which is not enough to fool a user.

The solution was to sandbox the window. This is possible by opening it from my own sandboxed iframe, as it keeps the sandbox in a top-level context! Configuring this without the allow-forms attribute so that it cannot submit the form, but we can still script and have same-origin access while the submission is blocked!

<h1>Click to continue</h1>

<iframe name="iframe" sandbox="allow-modals allow-popups allow-same-origin allow-scripts"

style="display: none;"></iframe>

<script>

onclick = () => {

iframe.open("https://example.com?nextUrl=javascript:alert(origin)")

}

</script>

Blocked form submission to ‘https://example.com/some-handler-doing-serverside-redirect’ because the form’s frame is sandboxed and the ‘allow-forms’ permission is not set.